Executive Functioning

The phone rings, but you’re in the middle of eating dinner, so you decide not to answer it.

You’re walking your child to school, on the phone with her pediatrician to schedule an appointment, while also brushing out her bedhead. On top of that, you’re thinking about what you’re going to make the family for dinner that evening.

You’re walking to the train station, hungry after a long day of work, and you pass a grocery store. You want to buy something to eat, but you continue walking because you know that if you go into the grocery store you’ll miss your train.

The above scenarios describe mundane things we do every day with very little effort. And yet, the cognitive skills required - a set of skills encompassed by the term Executive Functioning - are some of the most crucial to our daily functioning, and are far more developed in humans than in any other animal.

What is Executive Functioning?

One of the most famous psychological experiments of executive functioning is the marshmallow test, first conducted in 1972 by the famed psychologist Walter Mischel. In the standard retelling, children are told that they can either have one marshmallow immediately, or have two marshmallows if they wait 15-20 minutes. The increased reward in exchange for patience is a form of “delayed gratification.” Results consistently show that the ability to wait for a larger reward develops in early childhood - younger children tend to want their reward immediately, while older children are more capable of waiting.

Delayed gratification is just one of the many ways executive functioning is expressed in daily life. According to Adele Diamond, a researcher on executive functioning, there are three broad categories of executive functions: inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Inhibition includes delayed gratification, as well as other forms of self-control. Working memory - sometimes called short-term memory - refers to our ability to actively hold information in mind for near-term use. For example, we use working memory when we look up someone’s phone number, and recite the numbers until we are able to write them down. Cognitive flexibility means that we are able to switch our behaviors depending on our goals and immediate environment. We can speak loudly over the roar of construction while talking to a friend outside, and then quickly switch to whispering as we enter a library.

Why is it important?

We use executive functions when we form goals, plan, learn new skills, follow instructions, maintain focus in the face of distractions, monitor our performance, and when automatic instincts or responses may not be appropriate. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that executive functions are key to success in life. Executive functions are impaired in mental disorders such as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and addiction. Higher levels of executive functioning have been linked to greater success in school and in one’s career.

While executive functioning can appear to be automatic, as in some of the examples above, it typically requires effort and concentration. In some instances, we have trained ourselves through experience to exercise this capacity with great fluidity, such as making a host of real-time decisions when driving a car. In these cases, with experience, our behaviors no longer require conscious monitoring to be performed adequately. We can, usually, perform these actions or behaviors on autopilot. However, the ability to automate these functions is not without costs. When we develop habits, they can be hard to break or interrup. For example, consider how most people search on the internet: we open Google, type in search terms and then most likely click on one of the first few results. The first time we use Google, or any new platform, we must direct our full attention to it to gain an understanding of how to use it effectively, what it does, what it doesn’t do, and so forth. We think about what kind of terms we need to use to generate relevant results, and we examine the results. But once we gain enough understanding and experience, we put little thought into our actions, which are, by and large, repetitive. Only when our attention is interrupted, or something unexpected occurs do we call upon our executive functioning resources to step into resolve our experience. For online (and even offline) behaviors, we stand to benefit from understanding which of our behaviors have become habitual, and reflecting upon these behaviors and goals from time to time to ensure that our actions promote achievement of our goals in the manner in which we want to achieve them.

How is Executive Functioning tied to childhood development?

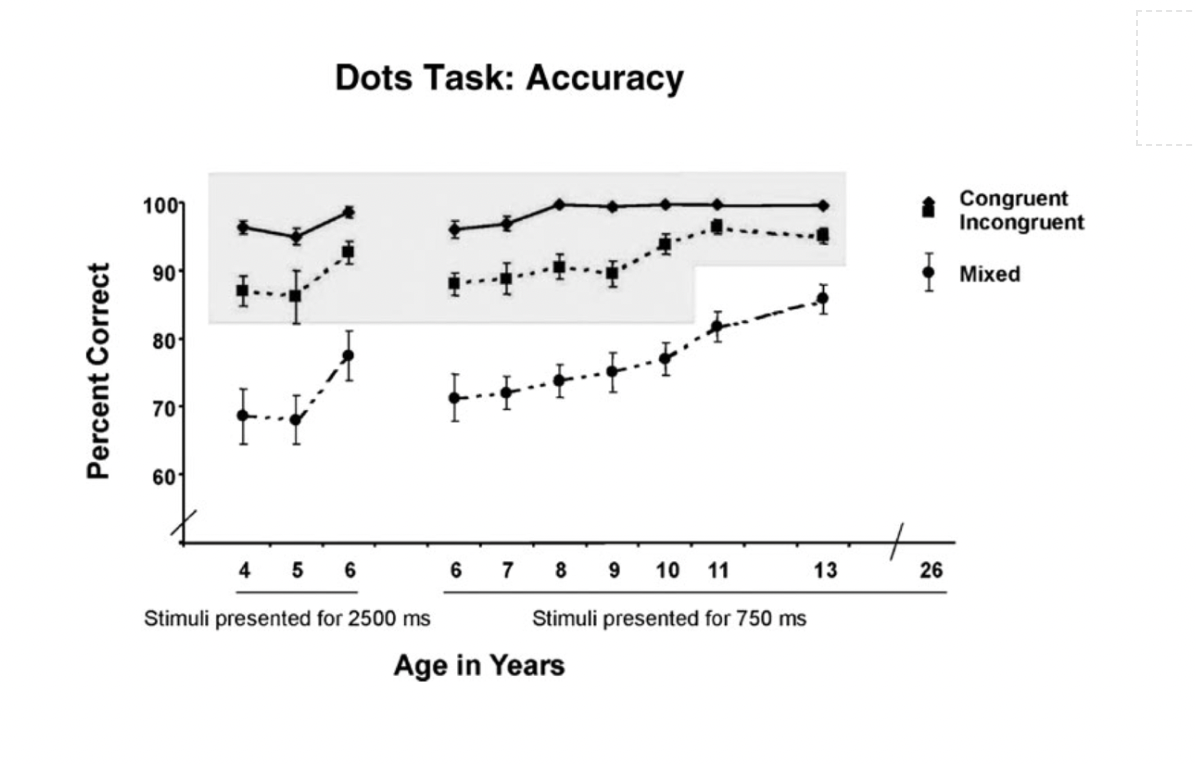

Childhood is a crucial time for the development of executive functioning. In a classic test of executive functioning, sometimes called the Hearts Flowers task, participants have to respond to what they see on the screen by pressing a button. In the hearts round, participants have to press the left key when they see a heart on the left side of the screen, and the right key when they see a heart on the right side. In the flowers round, the task is reversed: Press the left key when the flower is on the right side, and vice versa. Finally, there is the mixed round, in which both hearts and flowers appear, each with their own congruent and incongruent key-pressing rule.

Research shows that while adults show no difference in performance between the hearts and flowers round, children from age 4 to age 13 perform worse on the flowers round, which requires inhibition, than the hearts round. In addition, children perform worse than adults in the mixed round, which requires inhibition and cognitive flexibility, and this gap steadily decreases with age.

The fact that executive functions develop during childhood has deep implications for children’s relationship with technology. First, children are less able than adults to regulate their behavior. An adult may be able to stop herself from scrolling through social media so that she can finish a project with a tight deadline at her job. A child, on the other hand, might not be as well-equipped to stop so that he can finish his homework due the next day. It’s not that he is less interested in succeeding than the adult is, or more enamored with social media. It’s that his brain is actively changing, and the part of his brain responsible for self-control - namely, the prefrontal cortex - is not as robust as an adult’s is. Further, developmental trajectories are not identical across age or children. Individual and environmental factors, including family dynamics and cultural differences, can affect the development and maturation of various brain circuits that in turn govern these behaviors. An individual’s experience may require earlier or later use of executive functioning, resulting in different developmental trajectories.

Second, and on a more troubling note, technology that discourages the use of executive functions may prevent children from developing them in the first place. Many ways of using social media provide instant gratification - a like on a new post, or the endless availability of new content via infinite scroll - which means that users don’t need to employ inhibition or working memory. In adults, these skills have already been developed (albeit to varying degrees), but exposure at a young age to environments that don’t require them may hinder their development in the first place. Children can benefit from taking charge of and self-directing their attentional capacities. Online platforms often take on the role of harnessing attention, and often do not require children to exercise self-control of attention, nor to reflect or monitor their consumption behaviors.

Children are not just small adults - their brains are actively growing and being shaped by the world around them. A world that does not require executive functioning will not elicit its development. When considering best practices for using digital technology and regulating it, there is no one-size-fits-all approach - children and adults possess different capabilities, and will need different levels of safeguards when using technology.