The Problem

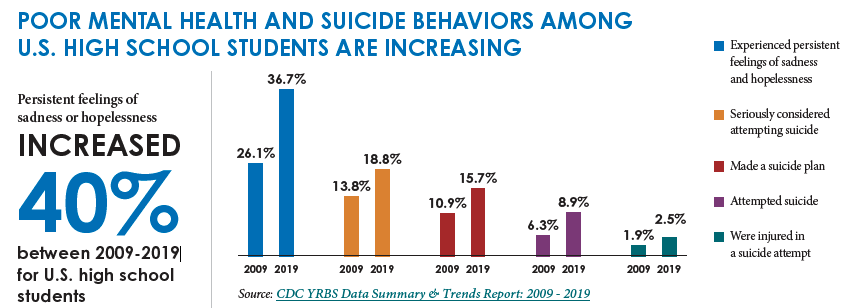

Human history is marked by struggles, mighty battles, dynasties, kingdoms, the rise and falls of nations, and outsized personalities. For most of our history, humans did not have access to modern medicine or science as we know it. Maternal mortality rates (mothers who pass away due to childbirth) were approximately 800 per 100,000 babies born, up until the 20th century, when modern medicine brought the rate down to about 10 per 100,000. When children and mother survived birth, in many parts of the world, one out of every two children never made it past 15, until the advent of modern medicine. By most any measure, daily life was indeed a struggle for most of the population, yet the limited data we have does not suggest that people were less satisfied, happy or fulfilled than those of us that live in modern society, a society marked by unprecedented safety and convenience. Advances in technology have dramatically improved outcomes in countless areas and led to the more than doubling of the average lifespan in most developed countries, with vastly enhanced quality of life. While no perfectly comparable data exists, some scientists have estimated happiness extending back to the late 18th century. Digitized text data was analyzed to create a valence (positive vs. negative) index, and using this valence, the researchers concluded that happiness was significantly higher from 1776 until the mid 20th century than it is today. Zooming in on the last few decades, modern measures of happiness show a marked decline beginning around the start of the 21st century. If we examine high school age, the decline starts a few years later, around 2011. Around this time significant changes begin to appear regarding how high school age citizens spend their time and how they feel, specifically, a decline in time sleeping and in-person interaction, an increase in time spent online, and a decrease in overall happiness.

Economists, social scientists, psychologists and other researchers have ideas as to why the decline is observed, but no consensus has emerged as to the relative contribution of factors proposed to account for the trends. Many of these factors are examined on the CBMS website and include: shifts in parenting and education; the digital revolution and penetration of connected devices; evolution of societal discourse; and economic challenges and wealth gaps, among other potential contributors. Many of these factors affect each other, perhaps amplifying certain trends. In other instances, some of the shifts may not be constant; in other words, some shifts may have occurred shortly after the turn of the century while others are currently in the foreground. These trends, along with the psychological mechanisms, abilities and components that accompany them, are discussed to provide a contemporary perspective of how humans respond and function in modern society. Modern society in our view is defined loosely as the boundary between the pre-internet and post-internet world, however, by no means should this be interpreted as excluding other important shifts in society that have been documented since the turn of the century.

A Snapshot of Modern Life

A mother walks down the street with her toddler in a stroller. The toddler begins to cry, leading up to a crescendo of high-pitched wails, flailing its arms around, and throwing cheerios at the strangers passing by. People start to stare. Flustered, the mother whips out her smartphone, opens the YouTube app and gives the digital babysitter to the toddler. The child goes quiet and stares intently at the colorful characters moving on the screen, a seemingly magical quick fix that distracts and captures the attention of the young child.

Two middle school friends sit next to each other on the bus ride home. Instead of conversing with each other, they pull out their phones to text their friends, and start showing each other memes and catchy TikTok videos. One friend pauses a video to respond to a message notification he just received, navigating from app to app, tap to tap.

A college freshman sits by herself at the cafeteria table of her college dining hall. She hasn’t met many people yet in her first week at University. Her roommate is often busy with her new sports team, and their schedules don’t overlap. She also hasn’t been able to have many conversations with the people in her classes. Everyone gets to the classroom a few minutes before the lecture starts, sits down, and pulls out their phone to respond to messages and check notifications, or opens up their computer to answer emails. She’s feeling a bit lonely, but decides not to think about it. Instead, she opens up Instagram and begins to scroll.

Most of us have seen, heard about, or lived the experiences in these vignettes. These stories give us a sliver of insight into what being digitally connected in modern life looks like. Our smartphones have become so entwined into our daily lives and socialization patterns that it is difficult to step back and think about how we might be affected, both positively and negatively, by using them. Screen-time, whether it be on FaceTime or TikTok or anywhere else, both reflects and drives our evolving modern society. Increased connectivity allows for more time talking to relatives and friends that live far away, but it also makes it easier for parents to check-in on their kids at all hours—a behavior that would have been unthinkable to generations past. Perhaps more important, however, is that TikTok, Instagram, and endless games, among other content, can suck hours of our time, time that we could use instead to interact with people face-to-face and develop substantive connections, enjoy nature, sleep(!), or simply spend some time with ourselves performing self-hygiene,; reflecting on our day, our goals, our relationships, what is going right and what is going wrong and how to approach our problems and improve our lives.

While technological change is the hallmark of growing up in the youngest generations, many other aspects of society and global affairs have also been changing and require principled study. Family dynamics including parenting, education, polarization, a terraformed information environment, and increasing income and wealth gaps permeate collective discourse. Wage growth over the past 30 years has been robust only for higher income earners, while middle and low earners experienced either no growth or a decline in real wages (inflation adjusted). The key differentiator, or gate, into the high earner bracket has been education, the requirements for which have risen, putting additional pressure on young people to complete as much education as possible to have the best chance at achieving economic security. While efforts are underway to scrutinize each of these aspects of society, not enough research has been completed in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relative contribution of each issue to the decline trend we observe in mental health and well-being.

In addition to conducting research into these important issues, the CBMS offers information and resources to demystify and clarify the research that has been done and how it may relate to well-being and mental health. Select a topic below for more information regarding trends and the connection between the topic and aspects of psychology.

Click below to learn more about each topic.