Mental Health in the 21st Century

Happiness and general mental health have been declining, particularly for younger generations. Although there are many possible sources for this decline, no census among researchers has been reached. Why haven’t researchers been able to identify a clear pattern? There are many reasons. Important to note, many studies collect data about a group of people’s mental health and social media usage habits. These studies may be insightful, but causality cannot be inferred. Studies that attempt to manipulate social media usage are also useful, but it is difficult to have a control or baseline, given that many people interact with or have interacted with social media. As well, social media is not monolithic, and social media usage differs greatly from person to person and from app to app. In addition to social media and more generally, the internet, some point to education and parenting for the decreases in happiness and mental health, although these claims neglect certain circumstances and contexts. Our website will look at these factors and the surrounding research in depth.Read more

According to polls, surveys and peer-reviewed research, happiness and mental health has been declining for many years, especially so for younger generations. Despite attempts to link various factors to the declines in measures of well-being, such as social media use or screen time, changes in parenting styles, changes in education, among other societal factors, no consensus exists as to exactly why these trends persist. While many of these phenomena likely contribute to the trends observed over the past decade, researchers do not yet have a strong grasp regarding the extent to which each may be responsible for the trends. However, shifts in how people spend time in social environments are undeniable. Our social worlds have been remodeled by technology, altering how and where we spend our time.

Parents and educators frequently attribute the steep decline in adolescent mental health that we’ve observed in the past 10 years to teens’ unhealthy relationship with social media, or digital technology more generally.

The connection between the two is intuitively simple–from online harassment to spending hours watching YouTube videos to gaining access to polarizing and otherwise disturbing content, it comes as no surprise that teens struggle more than ever with self-harm, depression, decreased attention spans, and social isolation. However, researchers have not been able to find a consistent relationship between social media use and mental health, and the evidence has often been contradictory.

Why haven’t researchers been able to identify a clear pattern? There are many reasons. The studies assessing mental health and social media often use data sets that have already been collected for other purposes. Results from these studies can at best point to correlations but correlations don’t always mean that one variable, say time spent on social media, causes changes in another variable, like mental health. These studies are typically not able to gain detailed information about use, such as, which platform and time spent on it, when the platform is used, how often the platform is checked, among other variables that assess motivations for use, life context and personality inventories. Very few studies have attempted to manipulate usage, and ever fewer could feasibly find a control group that has never used a smartphone or social media, especially among younger people. Consensus can only emerge when enough context is available to be able to understand how people coevolve with technology use; in other words, research that tracks a person - understanding various events or contexts aside from technology that might infringe on their mental health as well as various personality traits, and several measures of their use of digital technology over time. Simply knowing an amount of minutes or hours spent on social media is grossly inadequate to assess any relationship with well-being or mental health. Why? Social media is not monolithic. Different platforms are used for different reasons and may be associated with starkly different outcomes. Interactions and use may be biased towards positive, affirming experiences or highly negative, anxiety producing experiences. Some people may use excessively as a way to regulate emotions, while others exhibit more addictive-like behaviors. For these reasons, among others, far more detail is required around the use of specific platforms, and overall use and interaction with smart devices. For example, few studies examine contextual factors such as when people use certain platforms, how often, what they do on them (i.e. browse other profiles, post their own stories, view overwhelmingly negative information), along with other data about people’s lives that could account for shifts in mental health. We also need to know what people do when they aren’t online. Are people spending time in person with friends and family, exercising, making room for de-stressing and offline activities?

Other ideas that have been offered to account for declining mental health include shifts in parenting and education that have resulted in lower resilience, but these arguments often leave out other co-occurring trends at societal and economic levels. For example, the civility of public discourse has declined as polarization increases; widening wealth and income gaps threaten the financial security of young generations, for whom many economists predict will be less financially successful as their parents. Other researchers point to the disparity in mental health between rural areas and non-rural areas, suggesting that the inability to participate in online social discourse due to poor or lack of connectivity amplifies feelings of loneliness and despair. As a result, the answer is likely to be a plurality, and depends on the context - in some situations, certain types of excessive use may be toxic, while in other cases the feeling of being shut out from the social world may be the driving factor. Many of these topics, and more, are discussed on our website.

An Overview of Trends in Mental Health

Considering the global circumstances, it is not intuitive that mental health would be declining. The convenience of technology allows us to live with immediate knowledge, fast deliveries of food and goods, and modern medicine. However, younger generations have shown this trend of decline, more than older generations. Particularly, young girls, the LGBTQIA+ community, and minorities carry a disproportionate weight with mental health trends and are communities that research shows consistent decline in mental wellbeing. The CBMS looks to investigate these trends, and the possible contributing factors.

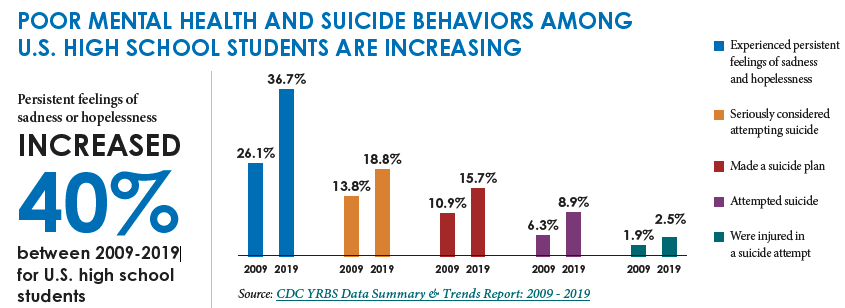

Taking an inventory of the various technological and other features of modern society, the trend in mental health may appear rather puzzling. Global scale conflicts have been absent since the end of the Second World War, and in the developed world by most measures, access to resources have increased dramatically. Most people have access to the sum total of human knowledge in mere seconds, and can purchase almost anything from their homes with the click of a button or tap of a finger. The opportunity to access goods and services, for communication and connection, has never been greater. Convenience for so many aspects of life has never been greater. Parents spend as much or more time and resources with and on their children, at least until around age six (and after college). More people are achieving higher levels of education. And yet trends in mental health in many developed countries reflect more what we’d expect in an economic depression or an unstable, declining, at conflict world. Surveys and research data examining anger, stress, sadness, and worry reported that these measures reached global highs in 2022, and current data does not suggest any changes to these trends. Yet, these trends in mental health appear to be selective. Older generations have experienced little change in subjective well-being. The younger generations have been disproportionately driving trends in unhappiness and declining mental health. And while most groups in younger generations experienced declines in mental health, young girls, the LGBTQIA community, and minorities bear the brunt of struggles with mental health, and especially so as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. These statistics are displayed in the below figures. Data: CDC; CDC YRBS Summary & Trends Report 2009-2019; CDC; The Atlantic.

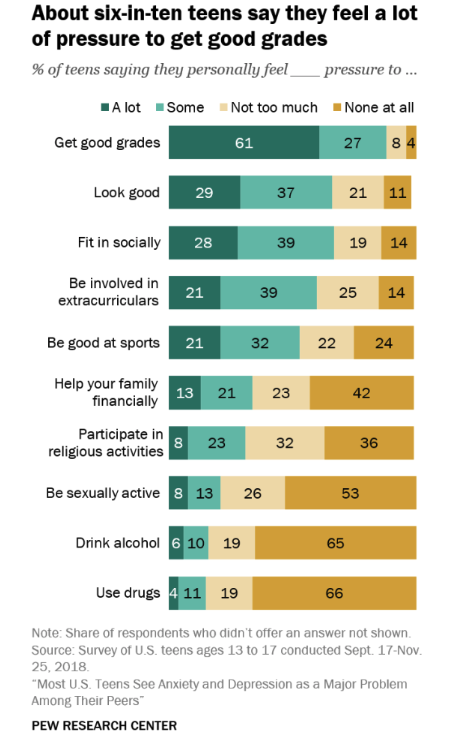

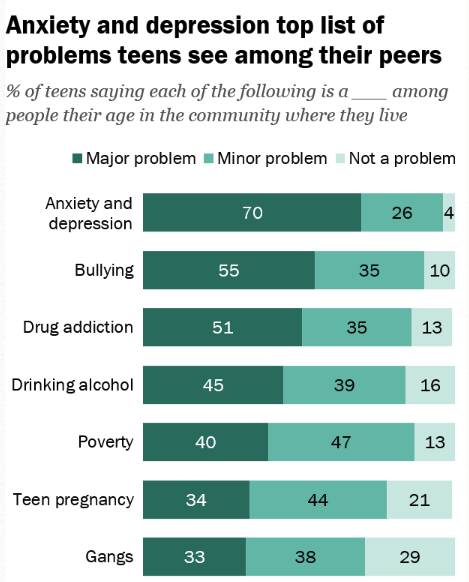

Despite a more educated population, with an abundance of learning opportunities online, access to more information than at any time in history, the increase in convenience for many aspects of life, certain and unique threats permeate modern society. Many young people have starkly different concerns than young people did a few generations ago. Data from polls examining issues that teens are most concerned about highlight the difference in mindshare of concerns between teens at the turn of the century and just a few years ago (displayed below, top: 2018 data; bottom: 2004 Data). The top concern a few generations ago was substance use, followed by social life (fitting in, appearance, popularity), followed by education and career. Today’s teens are highly stressed about educational concerns, such as getting good grades, followed by social life, and other activities associated with preparation for further education, such as sports and other extracurricular activities. Very little pressure is felt to drink or use illicit drugs, consistent with trends demonstrating a marked decline in alcohol consumption over the last ~20 years. Other polls measuring slightly different constructs suggest significant worry about mental health of peers and bullying, issues that did not appear in polls a few decades ago. Other changes over this 20 year period include a decrease in school fights, a reduction in bullying, the lowest rate of teen pregnancy since data has been recorded back in 1940, and far less drunken driving.

Many issues exist in modern society that were noticeably absent around the turn of the century, a time when mass shootings in schools were not commonplace, the science of climate change had not yet come into the public view, and networks that could spread and amplify information had not yet been invented. Society was significantly less polarized and public discourse was less toxic and confrontational. While wealth gaps have existed for decades, since 2000 the top 1% of earners in the U.S. have increased their share of national income from 18% to over 20% while the bottom 50% have seen their share of national income decline from just over 15% to approximately 13%. The gap, which was about 3% in 2000 is now greater than 7%. Income gains for the highest earning Americans have soared over 400% since around 1980 while all other groups have climbed at rates far below per capita GDP growth. Per capita GDP has grown 79% since 1980 (inflation and population adjusted) but after-tax income of the bottom 50% has risen just 20%, while middle income earners experienced just a 50% rise. The increasing gap contributes to a source of stress as it relates to achieving economic security for younger people, and their parents. The social world of adolescents has been remodeled by digital technology, requiring most teens to manage both their physical and digital social circles and reputations. The constant barrage of social information and social risks to avoiding online interaction, unique to young generations, may also contribute to teen angst. Together, the effect of negative information with its increased spread (resulting from algorithmic activities), and overall trends in parenting and society generally towards safety, paints a picture of an increasingly dangerous world. This view discourages many of the risk taking activities that foster resilience and coping capacity, and may distort the extent to which certain factors may affect our lives.

Other changes in society that have been identified as playing a potential role in mental health trends include shifts in parenting styles and a shift towards a "dangerous world" perspective, education, and digital technology use.