The Social Self and Digital Tech

According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, “children aged 8-12 spend 4-6 hours a day watching or using screens, and teens spend up to 9 hours”. Much effort is currently underway to examine the effects of different forms of screen use, content consumption, and interactions on social media and elsewhere on the internet. But to the extent teens (and certainly, many young adults) are spending up to nine hours a day on devices watching videos, or gaming or chatting, we also need to ask, what are they not doing? What is screen-time displacing? Are devices largely becoming a replacement for face-to-face interaction, or are they supplemental? How much time are children and adolescents spending outdoors compared to generations in which smartphones didn’t yet exist? Are there key aspects to psychological development that require experiential physical social environments that are being replaced by virtual experiences? While this is a pressing question it is as yet, mostly an open one.

The Developmental Importance of Social Connection

Psychologists do know the importance of early life connections to caregivers, often described both in scientific contexts and popular articles as “attachment”. Some of the potential outcomes of poor attachment have become rather clear over the course of decades of research. Once infancy gives way to toddlerhood and beyond, social relationships and support are potent predictors of both physical and mental health.

In-person social behavior, as measured by number of friends, time spent with friends and peers, including dating, among other activities, appears to be on the decline, especially so in the past ~10 years. Coincident with this decline is a decline in well-being, happiness and mental health. Many important questions arise from this observation. Can most people maintain strong social bonds, the kind of bonds that prop us up during difficult times, that are reliable, dependable and relatable, while engaging in extensive use of technology on a daily basis? Are people even forming these meaningful relationships in enough quantity, comparable to periods when mental health was more stable? Are the benefits of pseudo-synthetic relationships, that is, largely virtual relationships with real people, equivalent to those derived from physically being with other people? Will we find deficiencies in social development, including in perception, evaluation and functioning for generations that grew up in the 2010s and beyond? Have family dynamics been changed; do interactions between parents and children differ? And what other activities (e.g. time outdoors) are impacted by significant screen time, and are these activities related to well-being?

The Many Pieces of the Social Self

Some research groups have started piecing together the various relationships between social development, which includes experience and time spent in-person with others, and outcomes such as multiple dimensions of well-being and mental health, in addition to ability to function at work or more generally on a day-to-day basis. Much like a form of memory called procedural memory (think riding a bike, playing a musical instrument, driving a car, tying your shoes…), some researchers believe that the amount of time and form of experience play a significant role in refining and shaping development of not only skills like riding a bike, but social development that enables proficient perception and navigation of the social world. If children and adolescents spend less time with each other and with adults, the argument goes, then we should expect to see deficiencies emerge in various social domains. And because of the close link between mental health and quality of social relationships, it should not be surprising if we observe a decline in mental health and well-being.

These researchers point to a dramatic reduction in in-person interaction during childhood and through adolescence for generations that grew up and are growing up in the internet, specifically smartphone, connected world. The decline in in-person social interaction has been estimated at least 50% and up to 85% in extreme cases. Instead, adolescents are socializing online, often more than they would be in-person.

Despite these trends, limited research to date does not paint an open and closed case vis a vis the decline in well-being and reduction in face-time with friends. Nonetheless, some efforts suggest a relationship between changing social patterns and well-being, suggesting that we obtain a better understanding of these social patterns.

The Difficulty of Quality Screen Time

Why are kids spending less time together, and are they spending less time with their families? Some say that obligations prevent more face-time with friends, but data suggests that requirements such as homework have been stable or declining over the past few decades. Face-time also occurs with family, placing another spotlight on parent-child interactions. But just being in the same place doesn’t necessarily equate to quality time. A recent poll highlighted that 62% of parents admitted to spending too much time on their cell phone while with their kids, and an even larger percentage of parents said they feel addicted to their smartphone. Other surveys have found that the hectic modern lifestyle demands most of the family time, resulting in fewer hours of distraction-less, engaged and shared time. Though parental involvement peaks around 6 years old, some research suggests the most important period for engaging, shared family time is adolescence.

Online vs. In-Person Socialization

Among the crucial questions that need to be addressed are whether or not online socializing is equivalent in terms of social development as in-person socializing, and a link exists between a heavy screen diet and well-being. Research has been mixed and inconclusive. Some research shows that more screen time, specifically for kids 9-10 years old, results in stronger friendships. This cohort did not use social media, and social development and sensitivity accelerates in teen years, severely limiting the conclusions that can be drawn as it relates to well-being into young adulthood. While benefits derive from both methods of socialization, both past and more recent research detail some important differences.

What is different when people communicate online? Cues, gestures and reactions, together known as body language, send powerful signals to communicators regarding the effects of interactions. Online interactions are mostly devoid of these signals that are present during direct interactions. Substantial amounts of real-time feedback from fact-to-face interactions helps refine communication skills, especially amongst peers. Real-time interaction is just that — conversation unfolds naturally without the ability to heavily curate responses or reactions. In other words, people can exert significant control over an online exchange; what they say, how they say it, when they say it or if they say anything at all.

That sense of control vanishes during real-time, direct interactions in which one has limited time to plan a response or reaction. During face-to-face interactions we learn to cope with uncertainty in real-time, during which we are forced at times to navigate uncomfortable interactions. These experiences build a kind of interactional resilience that is not acquired in the controlled settings of online discourse, and may improve the calibration of tone and choice of words appropriate to the context. In extreme cases, avoidance and anxiety may be related to the surrender of control that face-to-face interactions require. The resilience associated with acquiring in-person communication expertise may not be developed in highly structured environments such as school settings in which expectations are fully delineated and for which students possess “scripts” for each class or environment.

Face-to-face communication also requires participants to handle (or at times, suffer) the consequences of interactions. Consequences of aggressive words can be completely avoided over a texting session, but are unavoidable when people are directly communicating. Gaining face-to-face experience enables proficient navigation in real-world in-person settings and increases comfort in this environment. The failure to gain enough experience may increase social anxiety that could persist into adulthood. School settings are important environments to establish these skills, however, it may be that the social skillset required in a structured context does not translate well into an unstructured context, in which expectations or goals are unclear.

Social Development and Social Life

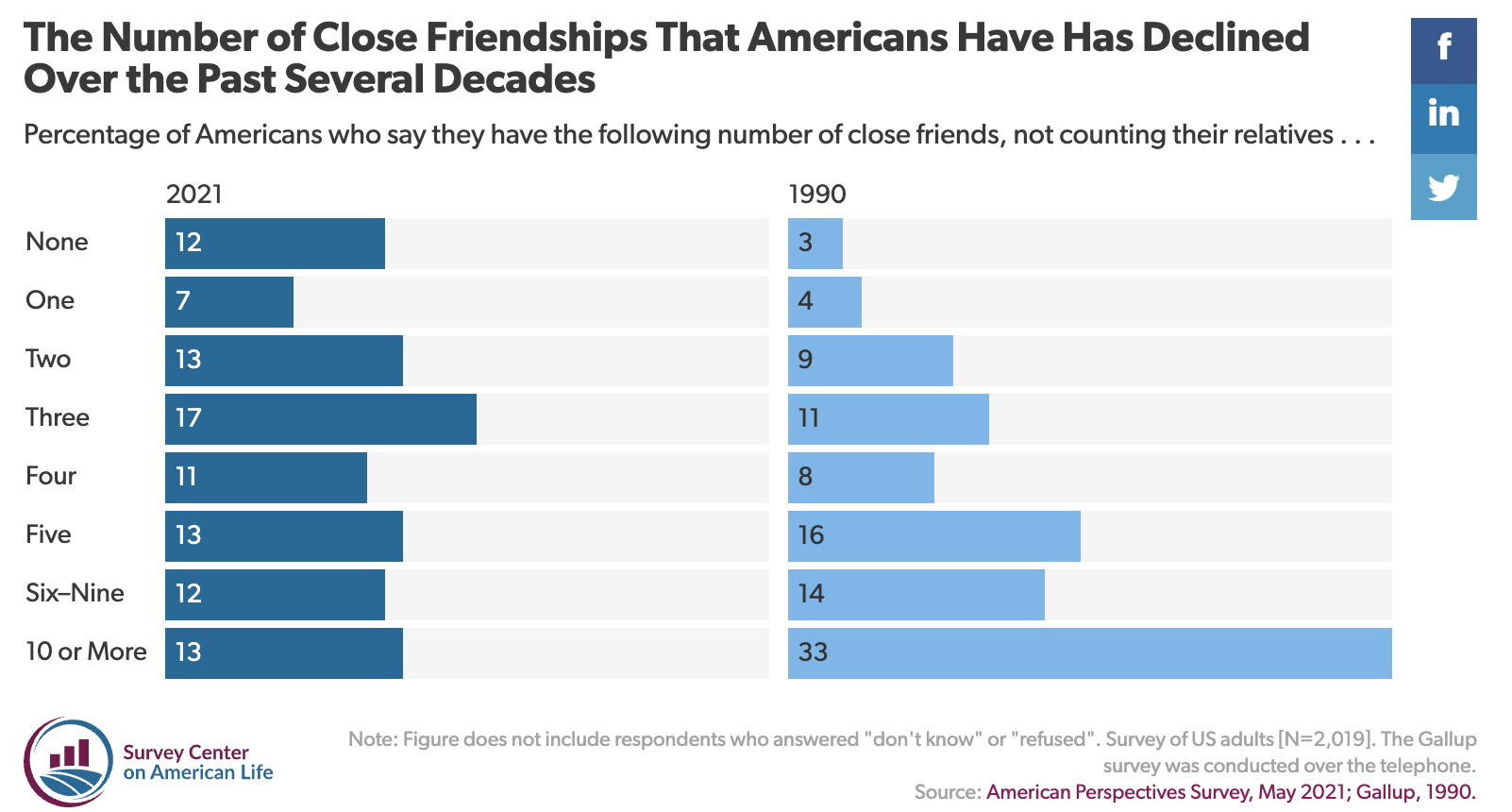

In regards to complex phenomena like social development, scientists are not content drawing conclusions from a single line of inquiry when many, many variables influence behavior, mental health, and well-being. In this instance, scientists seek other evidence that is consistent (converging evidence), or inconsistent, with the claim of decreasing in-person social interactions. For example, in addition to noting a decline in face-to-face interactions, we can examine trends in close friendships, and time spent alone. According to a 2021 survey conducted by The Survey Center on American Life, we find evidence consistent with the idea of a decline in social relationships. In 1990, just 3% of people reported having no close friends, and 33%, or ⅓ reported having 10 or more close friends. In 2021, the percentage of people reporting no close friends quadrupled to 12%; and just 13% report having 10 or more close friends (Fig. 1). Pew research reports that the majority of teens spend online time with friends (60%) every day or about every day, but just 24% spend in-person time with friends every day. Data from the long-term Monitoring the Future study echoes the Pew report. In this study, teens who spend in-person time with friends almost every day decline from 45% to 25% from 2005 to 2017 (Fig. 2). Instead of every 1 in 2 teens seeing their friends everyday, today just 1 in 4 see friends on a near daily basis.

Trends towards fewer close friendships do not necessarily lead to loneliness or risks to mental health. In fact, prior to the saturation of smartphones in the teen marketplace and ubiquity of teen social media use (specifically, 1978-2009; and 1991-2012), loneliness had been declining at the same time as the number of close friendships were declining. Troublesome trends in mental health come into sharper relief only after 2012. The trend of fewer friends and spending less time with friends began before smartphone penetration and climbed to a level in which just about every teen carries a device.

Correlation, Not Causation

While it is tempting to draw a line between increased usage of technology and a decline in social relationships and functioning, it is worth repeating that many variables influence behavior and well-being, and research doesn’t always point directly from cause to effect. For example, a study which examined parents’ and teachers’ perception of the development of social skills noted no significant changes from the years 1998 to 2010.

Then again, we also didn’t see a dramatic decline in mental health, sleep, and other measures until after 2010. A more careful reading of this research, however, reveals a trend which is more common today than during the study period. Specifically, that “social skills are lower for children who access online gaming and social networking many times a day”. In 2010, approximately 33% of youth (ages 15-24; Nielson) owned a smartphone, and of those only about half used the mobile web. In 2015, ~92% of teens owned a smartphone, and today, 95%. Teens spend far more time on social media now than they did in 2010, and most teens check social media at least once per hour. More recent work suggests that habitual checking of social media may impact brain development, and increases sensitivity to social feedback at a critical period in human development.

The Influence of Online Interaction on Brain Development

The implications of the changes in brain development are not clear. On the one hand, according to lead author Maria Maza, such changes could be adaptive to online social interactions and life. But on the other hand, we often do not behave in the same ways online as we do offline. So what are we adapting to, and is it at the cost of being proficient in in-person interactions? We don’t have definitive answers to these questions, but we can begin to assess some of the data regarding social perceptions, behavior and functioning with this idea in mind.

If in-person interactions are crucially important to building a robust social self, or, if significant social interaction online can undermine building or maintaining a robust self (or both), then an imbalance in favor of virtual interactions may manifest as deficits in social perception and functioning. We do indeed observe wide gaps between the youngest generations and people over 24 in the perception of the social self — that is, how people see themselves in relation to others, and how they actually relate to others. And the lack of being in possession of a robust social self is associated with a reduced ability to function and regulate in daily life. The reduced perception of the social self is accompanied by lower mood and outlook, represented by higher levels of anxiety and depression (see The Deteriorating Social Self in Younger Generations | Sapien Labs).

We might pose the question - are all the social lives and cues we see online authentic or are many highly designed and curated? That tenor of that question may be perceived as highly rhetorical by some adult readers, but consider younger people: if more social time is spent online than face-to-face, then we must forgive younger people for assigning greater reality to what they have more experience with - the online world. It follows that we should take seriously the prospect that the social environment encountered online by many young people is perceived as the main point of social comparison. With all of the tools available, and incentives for engagement, we observe a social impact arms race in which non-participation can intensify feelings of exclusion and non-belonging.

A Tricky Solution

So what’s an adolescent to do? Too much participation has been increasingly associated with negative outcomes vis a vis mental health. No participation can equate to disconnection and isolation, which is associated with poor mental health. Disconnection and self-esteem, not to mention the potential to be less proficient with technologies that define our modern landscape.

A practical answer is not to keep our children in the dark. Rather, a solution includes a multi-pronged approach. One prong involves a significant boost in educational efforts and guidelines that assist young people in navigating different aspects of the online world from the dangers to digital literacy to privacy to basic standards for interactions. Understanding how and why the social world online differs from our in-person experiences; how and why certain content is served to us; in addition to guidelines to assist in balancing our time spent online, may go a long way to improve our relationship to digital technology. A second prong includes awareness of the psychological effects of various activities; what does research say about the kinds of habits and activities most closely associated with improved well-being; and conversely what habits are most closely associated with negative impacts on well-being. A third prong is equipping adolescents with knowledge of various emotion and behavioral regulation techniques and how to deploy them in various circumstances.