Fact or Fiction? New Research Shows How Susceptible You Are to Fall for Misinformation

In 1998, a fraudulent article was published falsely linking the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine to autism. Despite being demonstrably untrue, this myth has persisted with real-world consequences - one recent study found an average increase from 1999-2019 of 70 MMR cases per month in the US.

This stunning example illustrates the urgent issue of misinformation susceptibility and persistence. Misinformation susceptibility describes how likely someone is to believe information that is untrue. At a time when misleading or downright false information can be shared across the globe with the click of a button - or flooded onto our screens by AI, - the effects of misinformation have never been more salient.

Introducing MIST: The Misinformation Susceptibility Test

In 2023, researchers at the University of Cambridge published the first ever scientifically-validated instrument to measure a person’s susceptibility to fall for misinformation. This tool, known as MIST, seeks to measure the test-taker’s general ability to discern true news headlines from fake ones. It works like this: the test shows you a series of news headlines and you have to decide whether they are real or fake. The real headlines are pulled from real news publications; the fake ones are AI-generated.

A key goal of this novel test is to standardize how we measure misinformation susceptibility so that more effective research can be conducted. In MIST’s first widespread application, the authors partnered with YouGov, a global research and analytics group, to administer the test to over 1,500 Americans across a wide range of demographics.

On average, people were able to correctly identify a headline as either fake or true two-thirds of the time. However, - and perhaps surprisingly due to their comparative lack of experience in digital spaces - only 9% of adults aged 65+ mislabeled half or more of the headlines compared to an alarming 36% of participants aged 18-29. This finding mirrors a trend whereby younger people are increasingly getting their news from non-traditional sources. For example, a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2023 found that 32% of this age group reports regularly receiving their news from TikTok. With anyone able to create content, no reporting standards to adhere to, and an echo-chamber algorithm at work, misinformation abounds - and sticks. Indeed, the YouGov test found that performance decreased in participants who spent more than three hours of leisure time online or who stated they received most of their news from social media sites like TikTok, Snapchat, or Instagram. Most Americans today spend 4 or more hours online for leisure purposes, with teens spending the most time at 7-8 hours per day.

It’s important to contextualize these findings within the scope and limitations of MIST. The head of research and analysis at the University of Cambridge’s Center for Science and Policy, Magda Osman, points out that the test forces people into a binary decision of real or fake, despite the fact that without further context, some of the headlines leave room for interpretation. Furthermore, whittled down to 20 questions, it’s difficult to determine whether or not different groups of people may be more or less susceptible to misinformation according to different topics. And while MIST seeks to measure a person’s susceptibility to blatantly false information, misinformation also includes misleading information: information that may not be entirely untrue but is presented in such a way so as to intentionally mislead the audience.

The Second Epidemic

We’re living in an unprecedented time of information overflow, so much so that during the COVID outbreak in 2020, the UN and World Health Organization sounded the alarm about a second epidemic: an infodemic. Infodemic environments are breeding grounds for the spread of misinformation, and a tool like MIST can help us understand who is most affected and why.

For example, researchers have advanced two broad theories explaining misinformation susceptibility, both of which are the subject of current scientific debate. The inattention account argues that people generally want to seek accurate information but the infodemic environment acts as a formidable barrier.

One reason for this is that with limited time and cognitive resources available to sift through an onslaught of (mis)information, people fall back on heuristic tools to make their decisions about what to believe and what to share. For example, Pennycook and Rand highlight the well-documented evidence for the illusory truth effect, an availability bias that demonstrates how our belief in the frequency or truth of an event increases with our exposure to said event. When our cognitive resources are taxed, we’ll also be more likely to make snap judgments based on perceived source credibility: in the world of social media, the authors point out that this can simply come in the form of social feedback like the number of ‘likes’ a piece of news content has. Research has also shown that our attitudes and beliefs are influenced by emotion, with emotional content increasing the nature of and speed at which we are likely to form our impressions and opinions (for an example of this tactic at work, check out the Bad News Game, described later in this article).

Through these mechanisms, our belief in what is true is susceptible to manipulation through algorithms and AI bots that repeatedly upvote, engage with, and expose us to targeted content designed to evoke strong emotional responses, regardless of that content’s actual veracity. Social media is the quintessential playground for this but popular media outlets aren’t far behind, rendering media literacy a crucial skill across the information landscape.

In contrast to the inattention account, the motivated reasoning account states that accuracy is actually not a primary driver of information-seeking but instead, people are (politically) motivated in their thinking. “The basic premise is that people pay attention to not just the accuracy of a piece of news content, but also the goals that such information may serve,” writes Sander van Der Linden in a 2022 review article for Nature Medicine. If information is viewed as being supportive of one’s goals (or conversely as undercutting one’s opponents), it is perceived as more plausible, regardless of actual veracity.

In addition to these theories, other researchers in adjacent fields, such as Judgment and Decision-making, have shown that accountability matters with respect to behavior. Online we are less accountable to others than we are when we are face-to-face with someone. Much communication is performative and with others whom we may not know well or at all. As a result, we are less likely to consider the consequences of our behavior online.

What Can We Do to Decrease Susceptibility to Misinformation?

Misinformation is incredibly sticky - once learned, it can be difficult to unlearn. However, research shows promising effects of interventions targeting just this problem:

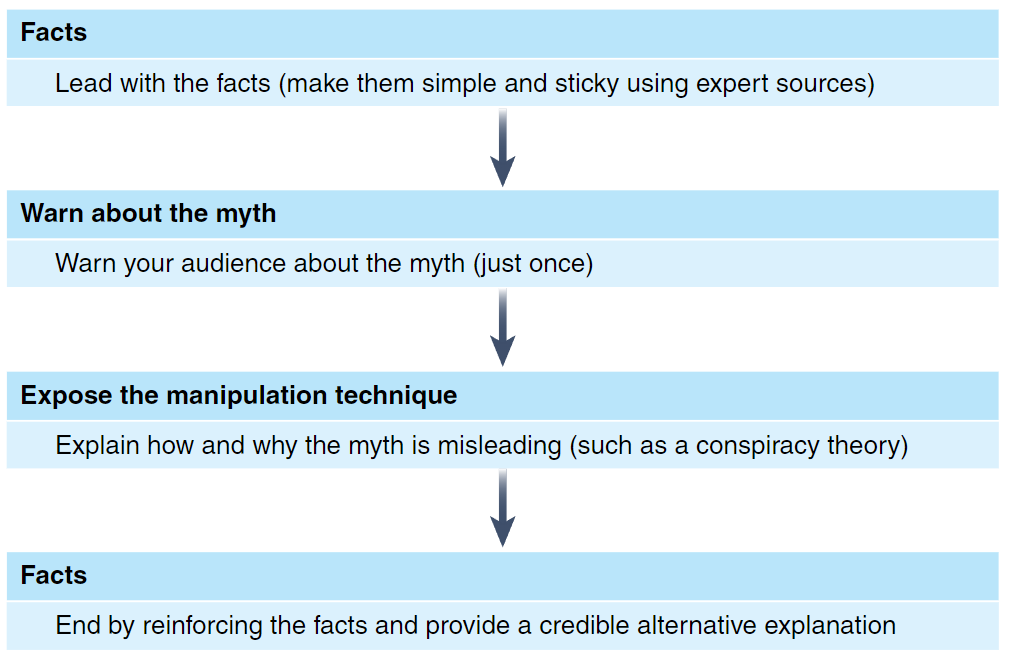

Debunking

After someone has been exposed to misinformation, correcting the falsehood with the facts has been shown to be an effective intervention. This is known as debunking because it occurs after the person has already been ‘infected’ with the misinformation.

Prebunking

Another even more promising intervention is known as prebunking: This strategy strives to proactively equip people with the ‘antibodies’ they need to fight misinformation, before they’re exposed to it.

These figures come from Sander van der Linden’s 2022 review summarizing what is currently known about the spread of misinformation.

It’s important to note that the protection of prebunking interventions are not without their limitations: their effects have been shown to wane over time. Like most vaccines, regular ‘booster shots’ can help increase and maintain immunity.

Living in an Infodemic: Tools for Fighting Misinformation

Are you curious about your own susceptibility to misinformation? Try taking the MIST yourself to see where you fall.

Are you a parent or educator? Encourage your kids to play the Bad News Game, an active (and extremely engaging!) prebunking intervention that puts players in the seat of someone who is intentionally trying to spread misinformation. Rather than inoculating players against a specific piece of false information, this game, developed in collaboration with researchers at the University of Cambridge, exposes them to six common misinformation strategies so that they can be better prepared to recognize and combat such tactics when they come across them in the real world.

Finally, the World Health Organization has created a series of open-access infodemic management courses to help fight misinformation, specifically as it relates to public health.

References

Common Sense Media. (2022). The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Teens and Tweens, 2021 [Infographic]. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/2022-infographic-8-18-census-web-final-release_0.pdf

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

Maertens, R., Götz, F. M., Golino, H. F., Roozenbeek, J., Schneider, C. R., Kyrychenko, Y., Kerr, J. R., Stieger, S., McClanahan, W. P., Drabot, K., He, J., & Linden, S. van. (2023). The misinformation susceptibility test (MIST): A psychometrically validated measure of news veracity discernment. CrimRxiv. https://doi.org/10.21428/cb6ab371.d919c9a1

Matsa, K. E. (2023, November 15). More Americans are getting news on TikTok, bucking the trend seen on most other social media sites. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/11/15/more-americans-are-getting-news-on-tiktok-bucking-the-trend-seen-on-most-other-social-media-sites/

Motta, M., & Stecula, D. (2021). Quantifying the Effect of Wakefield et al. (1998) on Skepticism about MMR Vaccine Safety in the U.S. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/7wjb2

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The Psychology of Fake News. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007

Sanders, L. (2023, June 29). How well can Americans distinguish real news headlines from fake ones?. YouGov. https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/45855-americans-distinguish-real-fake-news-headline-poll

Thompson, D. (2024, April 25). TikTok Riddled With Misleading Info on Health: Study. US News. https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2024-04-25/tiktok-riddled-with-misleading-info-on-health-study

Thompson, J. (2024, February 20). How Susceptible Are You to Misinformation? There’s a Test You Can Take. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-susceptible-are-you-to-fake-news-theres-a-test-for-that/

van den Berg, H., Manstead, A. S. R., van der Pligt, J., & Wigboldus, D. H. J. (2006). The Impact of Affective and Cognitive Focus on Attitude Formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(3), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.04.009

van der Linden, S. (2022). Misinformation: Susceptibility, spread, and interventions to immunize the public. Nature Medicine, 28(3), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01713-6

World Health Organization. (2020, December 11). Call for Action: Managing the Infodemic. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/11-12-2020-call-for-action-managing-the-infodemic