Tolerance of Uncertainty

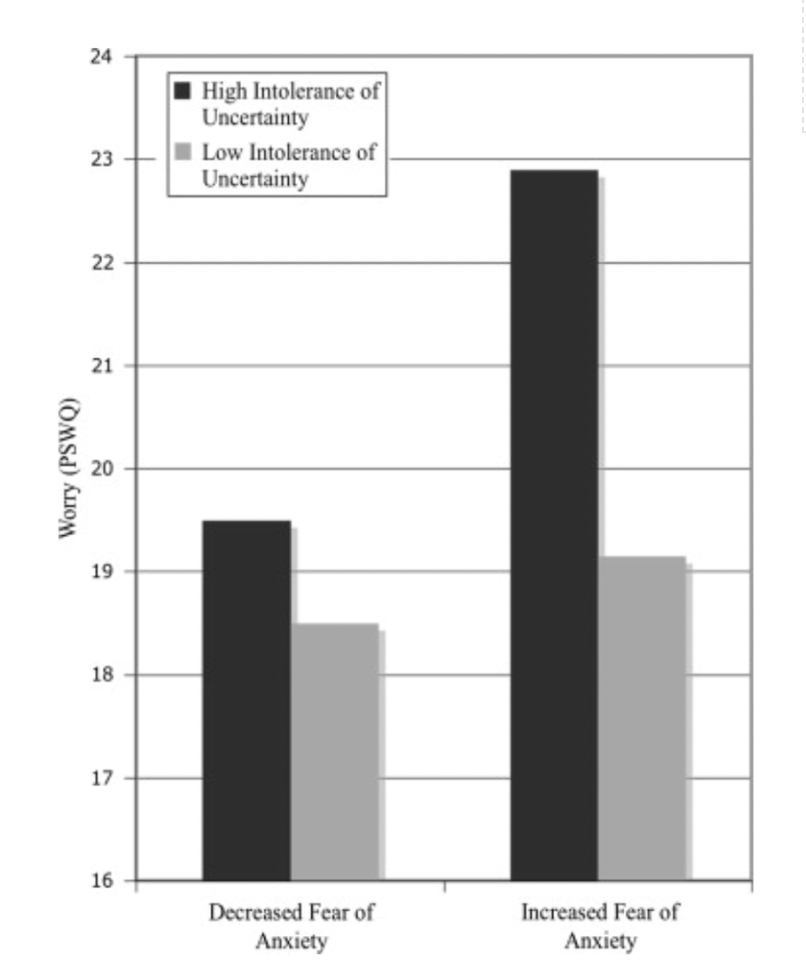

High intolerance of uncertainty in combination with fear of anxiety predicts higher worry scores. Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. (2009)

What is Tolerance of Uncertainty?

Why is it that some people fear change while others embrace it? How is it that some people shrug off the unknown and keep moving forward, while others are paralyzed by not knowing? Psychologists use a measure called Tolerance of uncertainty to assess a person’s cognitive, behavioral, and emotional reactions to uncertainty. Intolerance of uncertainty denotes negative beliefs about uncertainty and is predictive of thoughts, moods, and behaviors, such as anxiety and worry. This concept sheds light on causes of worry and anxiety, and the extent to which different people can react differently to the same amount of uncertainty. Uncertainty can derive from different aspects of experience and these aspects may result in differential emotional, behavioral, and cognitive outcomes.

Worry and uncertainty are inescapable throughout a lifetime. Prolonged and intense worry can be detrimental to mental health, given its predictive role regarding anxiety in both children and adults. As a result, understanding factors that contribute to problematic worry is essential for appropriate choice of interventions and treatments. However, like anxiety, a tolerable amount of worry has an evolutionary function in that small amounts of anxiety direct attention towards and motivate healthy behaviors to address the cause(s). Too much anxiety, or worry, can exceed a given individual’s tolerance, thereby becoming maladaptive. Tolerance of Uncertainty enables researchers to estimate and understand individual differences in perceptions of uncertainty, and how these differences can result in differential outcomes for the same experiences or events.

Intolerance of Uncertainty and Anxiety Disorders

Intolerance of uncertainty predicts several outcomes and behaviors, such as the strategy one is likely to deploy when confronted with uncertainty. High intolerance of uncertainty or IU is linked with maladaptive coping strategies. Maladaptive coping strategies are problematic or unhealthy coping mechanisms in response to anxiety or stress. These strategies are correlated with higher levels of anxiety and depression. Some research suggests that maladaptive coping mechanisms mediate the relationship between IU and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). This relationship suggests that maladaptive coping strategies may be an important link between intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety. Critically, high levels of intolerance to uncertainty are a significant predictor of worry in both adults and children. High intolerance of uncertainty is transdiagnostic across anxiety and depression, meaning it is a trait seen in both, so understanding its role in these disorders is important.

Student levels of worry have increased significantly over the last two decades. Davey et al., 2022

Worry is often accompanied by uncertainty, and while little research tracks intolerance of uncertainty in student populations, worry is frequently measured. The above figure displays a marked increase in worry in student populations over the last two decades. Many explanations have been advanced by sociologists, psychologists, and other scientists, who suggest the pattern is likely due to shifts in our rapidly evolving society, including fundamental changes in our information environment, evolving cultural and social norms, geopolitical conflicts, income and wealth distribution trends, and the emergence of and focus on existential risks. Contemporary students lead very different lives than students in 2000, who developed under different circumstances, most notably without the internet and smartphones. Nonetheless, researchers are working to better understand the specific circumstances under which worry becomes pathological. Pathological worry is a main diagnostic criterion for anxiety disorders, which have also risen over the same time period.

Uncertainty in Today’s World

Adolescence is a time of rapid change and sensitivity, and the modern era is unlike any other. Among the myriad reasons why, perhaps the most impactful is the connection to today’s information environment, which is always on and has evolved according to an attention and engagement focused incentive structure. Much information reaching teens is social in nature or features a degree of uncertainty, given the role uncertainty can play in inviting more attention. Uncertainty is a primary cause of sampling, meaning that when uncertain, we are motivated to seek more information to attempt to reduce uncertainty. When the environment we sample from is plagued with misinformation, ambiguous or conflicting information, or is overwhelmingly social or negative, our uncertainty may not be reduced as much as we expect. This can cause excessive sampling in a feedback loop that can exacerbate the effects of uncertainty, leading to anxiety. Adolescents are especially sensitive and have been shown to oversample when high on intolerance of uncertainty. Having a plan prior to seeking information can help both cognitively and emotionally. Information encounter strategies help us to avoid oversampling; enable us to exert control over the amount of information we are willing to consume in a given encounter; to recognize that uncertainty and complexity may not always be resolved; and that everyone must live with some level of uncertainty.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic was a period of unprecedented uncertainty for younger generations, particularly in the early stages when little was known about the risks or effective mitigation techniques. Research on IU during this period demonstrated higher levels of anxiety than periods preceding the pandemic. During most of 2020, uncertainty was unavoidable as the world went through phases of shutdowns and reopenings. Varying levels of Intolerance of uncertainty are believed to have played a role in how individuals coped with and responded to the pandemic. Individuals with high intolerance of uncertainty had higher health anxiety and COVID concerns throughout the pandemic. While under more normative circumstances such a profile may be maladaptive, for some individuals, the extenuating circumstances make such anxiety adaptive, demonstrating nuance regarding whether anxiety is beneficial or harmful. Higher COVID concern is associated with better adherence to COVID mitigation policies and mask-wearing, thus reducing the risk of infection. Others with high IU were also more likely to seek medical care and utilize mental health resources. Yet in other individuals, high IU was associated with maladaptive coping strategies, suggesting that other factors in addition to IU determine behavioral, cognitive, and/or emotional outcomes.

The ultimate impact of COVID-19, including not just the fear of infection or the effects of infection, but the policies implemented (or not implemented) and the social controversies is yet to be fully researched. Nonetheless, the period represented a time of great uncertainty, for which some individuals were predisposed to handle effectively while others less so.

Changing Tolerance

High intolerance of uncertainty is associated with a higher risk for anxiety disorders, depression, and other mental illnesses like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Being precise about the specific form of uncertainty (probability, ambiguity, complexity, etc.), is important not only in understanding potential causes but also in the selection of intervention or treatment options. In many contexts, tolerance can be increased, thus reducing the propensity for worry and other negative thought patterns that can result in anxiety or depression. For example, acute stress has been shown to influence decision-making such that under stress people choose options characterized by greater uncertainty more frequently than in low stress conditions. In low-stress conditions, people tend to select safer, more predictable options. This finding indicates that context, such as being under stress, can induce a greater willingness to engage with uncertainty, which may lead to greater learning. More frequent exposure to uncertainty is another factor that can alter one’s tolerance of uncertainty, due to experience and learning, especially within a domain.

Women typically demonstrate higher levels of intolerance of uncertainty and worry compared with men. Worry, in particular, is influenced by individual differences, including but not limited to personality traits, coping strategies, and emotional regulation. Further research is needed on IU to determine how individual differences relate to this measure, and how malleable the trait is over time and in response to interventions.

Further research will also be needed to clarify the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and worry, and the circumstances under which the risk of anxiety disorders and other mental illnesses is increased.

Keywords and Terminology

IU - Intolerance of Uncertainty

GAD - Generalized Anxiety Disorder

SAD - Social Anxiety Disorder

OCD - Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Citations

Birrell, J., Meares, K., Wilkinson, A., & Freeston, M. (2011). Toward a definition of intolerance of uncertainty: A review of factor analytical studies of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1198–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.009

Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. (2009). The role of fear of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in worry: An experimental manipulation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(3), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.004

Byrne, K., Peters, C., Willis, H., Phan, D., Cornwall, A., & Worthy, D. (2020). Acute stress enhances tolerance of uncertainty during decision-making. Cognition, 205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104448

Carleton, N., Mulvogue, M., Thibodeau, M., McCabe, R., Antony, M., & Asmundson, G. (2012). Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(3), 468–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.011

Davey, G., Meeten, F., & Field, A. (2022). What’s Worrying Our Students? Increasing Worry Levels over Two Decades and a New Measure of Student Worry Frequency and Domains. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46, 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10270-0

Hearn, C., Donovan, C., Spence, S., & March, S. (2017). A worrying trend in Social Anxiety: To what degree are worry and its cognitive factors associated with youth Social Anxiety Disorder? Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.052

Hirsh, C., & Mathews, A. (2012). A cognitive model of pathological worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(10), 636–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.06.007

Matta, S., Rogova, N., & Luna-Cortés, G. (2022). Investigating tolerance of uncertainty, COVID-19 concern, and compliance with recommended behavior in four countries: The moderating role of mindfulness, trust in scientists, and power distance. Personality and Individual Differences, 186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111352

Rettie, H., & Daniels, J. (2021). Coping and Tolerance of Uncertainty: Predictors and Mediators of Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Psychologist, 76(3), 427–427.

Sebri, V., Cincidda, C., Savioni, L., Ongaro, G., & Pravettoni, G. (2021). Worry during the initial height of the COVID-19 crisis in an Italian sample. The Journal of General Psychology, 148(3), 327–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2021.1878485

Songco, A., Hudson, J., & Fox, E. (2020). A Cognitive Model of Pathological Worry in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23, 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00311-7